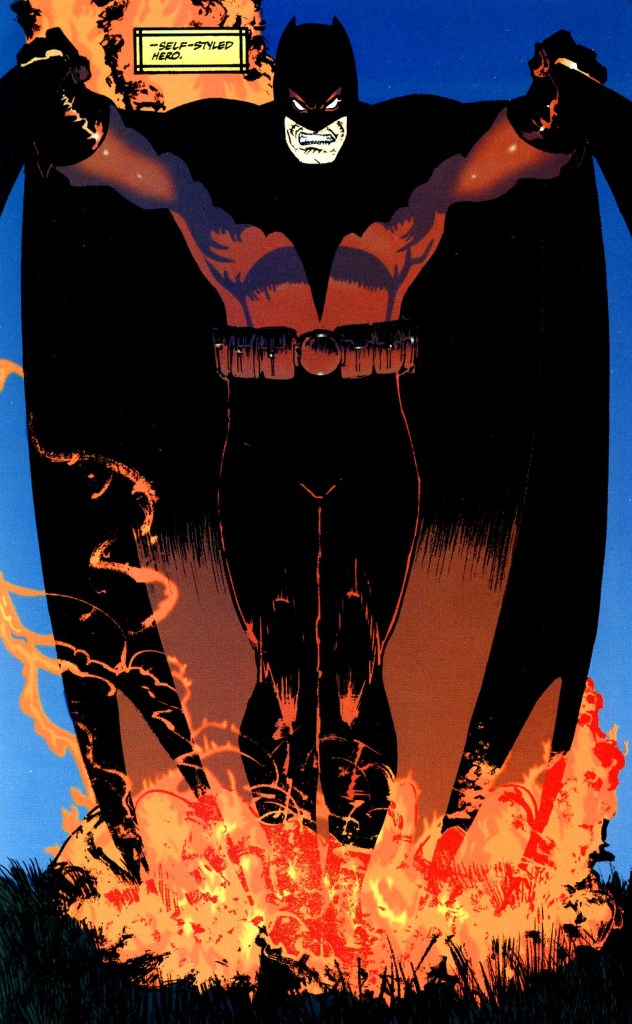

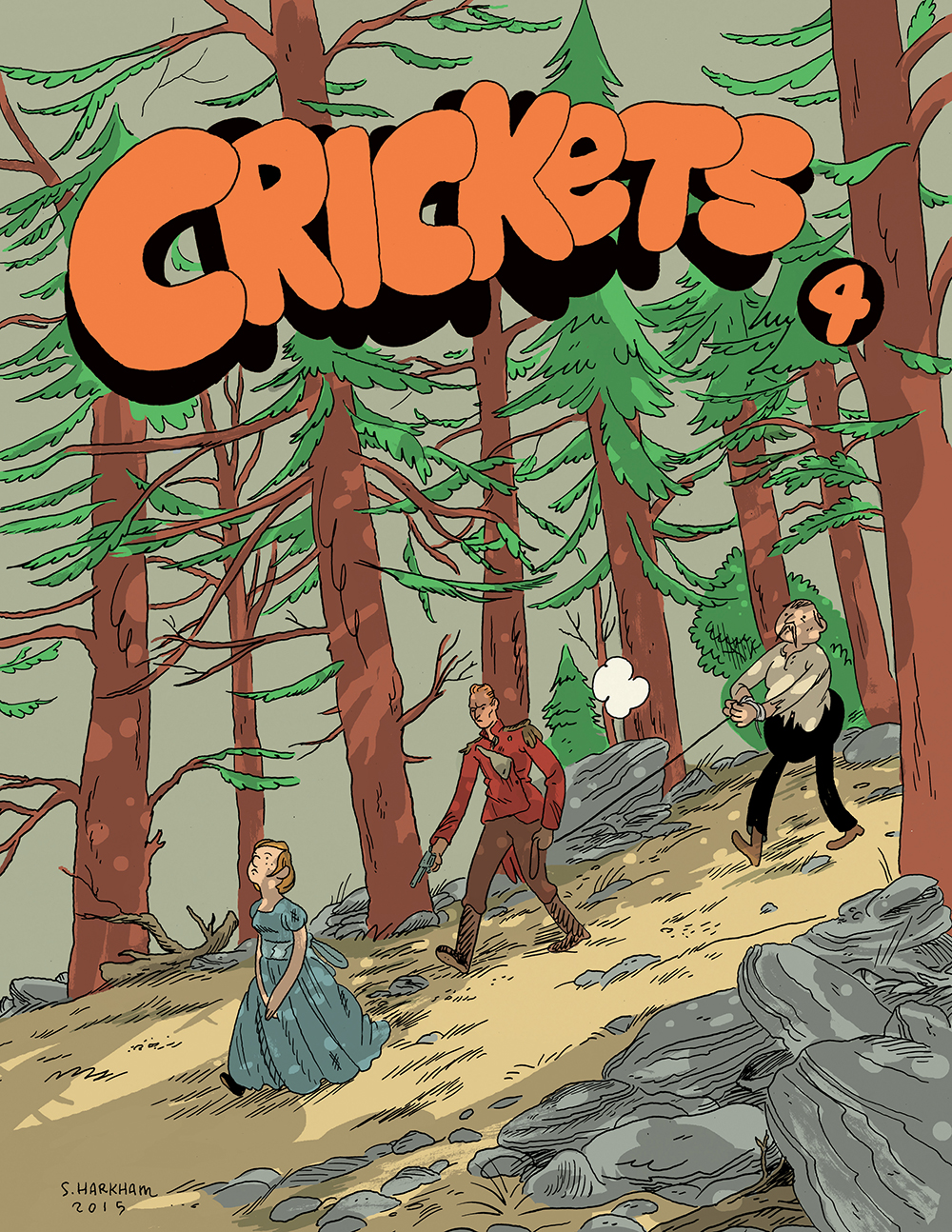

The American film set motivates and cages the cast of Sammy Harkham’s Crickets #4. The actors, crew members, director and writer all have agreed to make a film called Blood of the Virgin, even when it’s clear to them this film will be garbage, and it’s difficult to do. They, like any American, are just chained to the idea of success. The notion of working on a Hollywood production to either be placed in front of the camera or control its every movement is intoxicating to a point of grand illusion. But Harkham never explicitly states this illusion. He only alludes to it through small nods, mostly when characters comment to one another about the film’s progress, asking if what they’re doing is even good. For the most part, it’s our own understanding of why anyone would agree to a Hollywood production that suggests these characters’ reasons for working. We just know, because we live in their world, that they are after power and a chance to be understood.

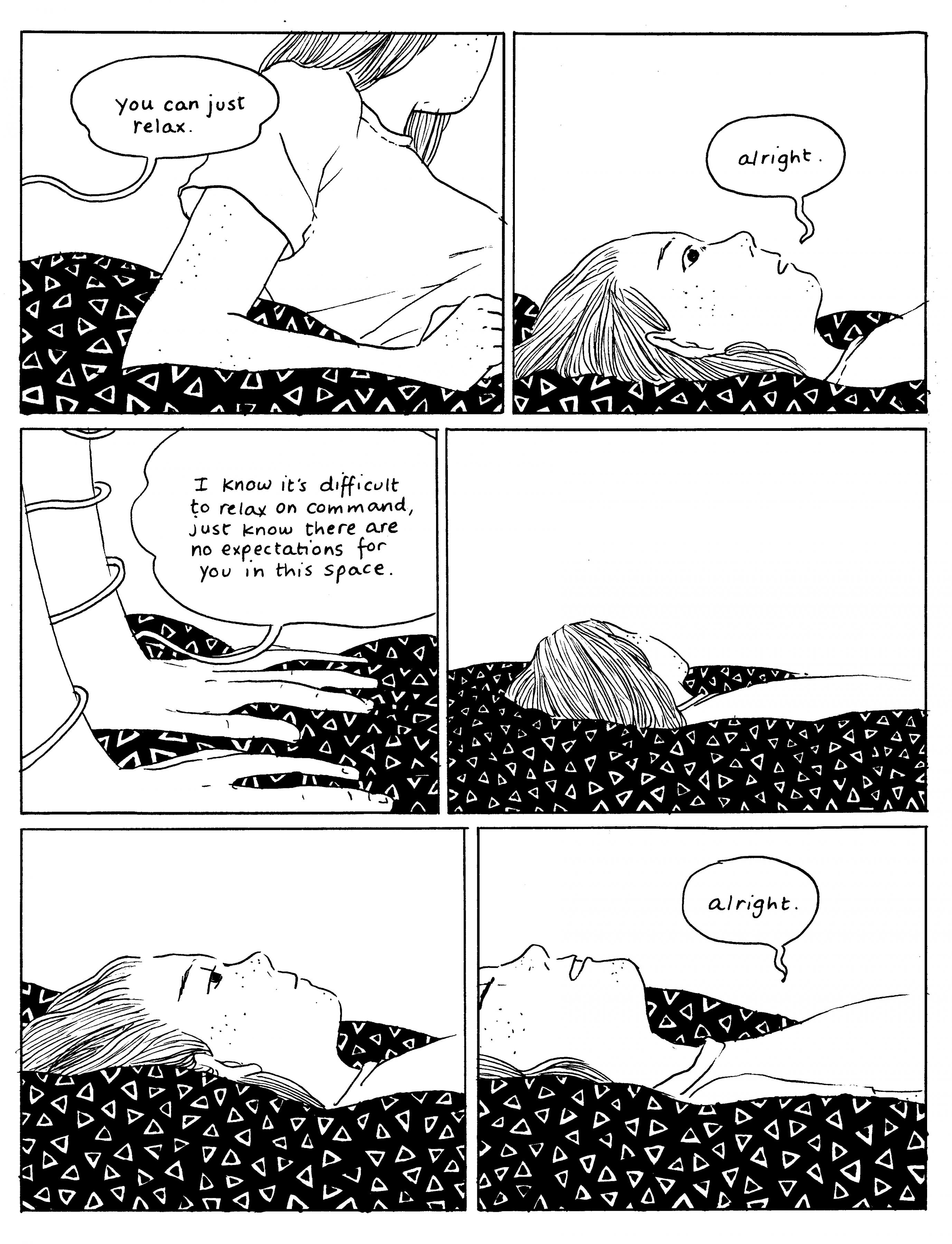

On set, they adhere to a budget and a script, and the location commands them. Harkham frames it all through a series of tight panel grids, confining this cast of several to a shared setting, bouncing all the players back and forth between each other. He just guides us through these scenes as they happen, introducing characters in passing, giving us the briefest hint of what it is they contribute to the production. There are insults thrown, jokes shared, and Harkham crafts clever gag strips around them, despite already committing to a larger frame of dense, 16 to 20 panel comic pages. This choice layers a feeling of confinement. Characters find themselves hyper-focused within 3 to 4 panel strips as a larger operation of page design exists all around them, influencing their movements. In ways, Harkham’s characterizations subtly suggest who his cast members really are, but because they’re players in short strips their involvement often leads to a punchline.

These punchlines, while funny, can be fairly illuminating. They can straddle a few angles, and be complex. When the writer, Seymour, is asked to “approve the camp set,” he simply lights a cigarette and smashes what’s in front of him. Harkham, in three panels, makes us laugh, and externalizes Seymour’s angst of being subjugated by the film’s director.

Seymour is the creator of Blood of the Virgin, yet he needs the director, Oswald, to make his movie, even though their visions don’t always correlate. Blood of the Virgin pairs these men together (as the issue’s cover might suggest), but it’s a conflict of power, of who exactly is in charge of this thing and what he wants, that disrupts their relationship and introduces reality to everyone else’s magic moment. Oswald argues with his lead actor because of a difference in creative choice, and the actor reacts by storming off, asking “is that how you see me, you lousy pecker-wood piece of shit?”. That actor, because of the reality of who has power over him, loses his grasp on his own perception of himself. He may be a creative contributor, but Oswald decides how the audience will see him.

Ironically, this display of authority unseats Oswald. When reports of turmoil between the lead actor and the director reach the film’s financier, it’s decided, by this figure of ultimate authority, that Oswald is unfit for the project, and Seymour is handed the role. Which is what Seymour secretly wants, but with the position he finds how authoritative he must be. It’s a realization Harkham cleverly illustrates when Seymour, as director, must decide whether a take was good or not, and he hesitates in his answer with the entire crew awaiting his response. The lack of confidence Harkham draws on Seymour’s face says it all. That he hasn’t really considered what a director does, but assumed he was capable of it.

At home, Seymour has a wife. She’s introduced as a woman masturbating on a couch despite her baby crying in the other room. Harkham frames this sequence by starting with a closeup on the kid, zooming out, cutting to a large, wide panel of the wife, and then zooming in on her and her ecstasy. He’s transitioning from one image to the other as well as crosscutting them. As a housewife, this mother has great responsibility, but this responsibility can be a cage. As we know, living in our world, plenty of housewives have wanted more, whether professional fulfillment or social freedom. Their position, though some many enjoy it, can be a personal limitation, especially when the husband gets to leave and pursue what he wants. Here, though, Harkham shows this character taking control by attending to herself even though a responsibility requires attention. That she’s doing so over the cries of her child feels a bit disturbing, but it makes the act even more rebellious. It shows that with Seymour away, she isn’t lost.

The comic ends with Seymour driving a drunk Oswald home through a desert town outside of Hollywood. A place known as “the palm of God’s hand,” somewhere you imagine great things are possible so long as they aren’t crushed. This is after they’ve fought, and Oswald has lost his position. It’s at a point when Seymour may have a right to ignore the guy. He doesn’t. He drives him home and dumps him on his front lawn. It seems harsh to do it that way, but the fact is Seymour was there when no one else was. He’s using his ability as a human being to care for someone else, in some way. You don’t know if this is where their relationship ends or just takes another turn, but you get the sense there’s some fact found. That off the film set they’re still connected. That they have some power over one another.