I wrote a piece on Butcher Baker, the Righteous Maker months ago, and some time after an interview with the book’s artist fell into my lap. Mike Huddleston comes from that Kansas City crew of comic creators, and in some ways, he may be one of the more developed of the bunch. Attending art school in KC, Huddleston gained much of his motivation through some sort of rebellion – being looked down upon by professors for his admiration of comics.

“I spent the first year of college arguing with teachers, putting comic books under their noses, but receiving only a begrudging acknowledgement of the artistic merit of the work,” says Huddleston. “It was frustrating, especially as I was in a commercial illustration program- do you think painting a car for some magazine ad is more creative then the work in a painted graphic novel?”

In his last year of school, at the age of 21, Huddleston started to get work at DC Comics. He would describe the early introduction to the comics industry as a “crash course.”

“To work in comics, you have to be able to produce a huge volume of work, especially if you are taking on more than just one of the chores (penciling, inking, covers, etc.), and I wasn’t ready. At all,” says Huddleston. “The work I did back then wasn’t very good (you can ask Dave Johnson), and ultimately that first year in comics proved to be a false start as I didn’t work in comics again for another 5 years.”

Which leads to this quote:

“I was torn on my direction.

“I looked again at someone like Bill Sienkiewicz who could move effortlessly between the worlds of commercial illustration and comics, and I couldn’t decide which field to focus on. Eventually I went with what I loved and just hoped it would work out. Since then, I feel like I’ve been figuring things out and making my mistakes on stage, with each project focusing on a weakness or some new idea and just hoping I don’t bomb so badly I’m never hired again. So far, so good.”

Today, Huddleston collaborates with writer Joe Casey to produce the comic book series Butcher Baker, the Righteous Maker, and he also provides art for the Dark Horse adaptation of Guillermo del Toro’s The Strain. What follows is a conversation between Mike and I in which we cover some of his feelings about comics and the current state of things as well as Butcher Baker.

Read on.

Alec Berry: Before I really start handing out questions, I want to mention … you haven’t done that many interviews. I Googled for all possible “Mike Huddleston Interviews,” and I think I came up with like two. I just find it odd that a guy like you – with numerous years of experience – hasn’t really been interviewed much nor has your work really been covered.

Your name just doesn’t seem to be tossed around a lot, you know. So, do you see yourself as someone “under the radar,” or am I just reading the wrong comics blogs?

Mike Huddleston: No, I think that’s a completely fair assessment.

I don’t know exactly what or why that is, but I think the fact that I can be slippery as far as styles go may be a part of it… also I’ve never been a part of some big, major comic event, so I haven’t had that intense spotlight that comes from touching those really famous characters.

It’s not something I particularly worry about though as I am continuing to work on great projects, and I am finding more and more opportunities to really let loose like in Homeland Directive, and Butcher Baker, the Righteous Maker.

AB: You mention the spotlight that comes with famous characters … Something Joe Casey mentioned in an interview was how when you’re out of the spotlight, you have room to run and experiment because there’s not really any expectations placed on you.

It seems most comic books, especially from Marvel and DC, strive to keep a straight, normal look to please readers. You’re an artist who’s adopted numerous styles over the years. What do you think of a house style?

MH: This is actually something I’ve thought a lot about as I’ve tried different styles; whether it was a strength or a weakness. Generally, yes, people don’t want surprises in the things that they like. They want McDonalds to taste like McDonalds no matter where in the country or world they are. You know, it’s just good marketing. It’s good business for artists like Jim Lee or Alex Ross to always look like themselves as fans know what they are getting, and for that matter when an editor is planning a team for a project he can hire an artist with the idea of getting “X” style from him. But those are decisions made for business, not a cultural enhancement of comics as an artform.

I’ve always described my approach to others as “great for personal artistic growth, but terrible for business.” The revelation for me recently has been the response to Homeland Directive and Butcher Baker, where instead of trying out a single idea or technique on a new project, I tried everything I was curious about all at once. People really seemed to notice, and many discovered me for the first time- SO maybe there is a way to make fans happy AND move things ahead a little.

AB: I think it’s possible to do so. I think many artists push their selected mediums everyday in some way, but really, only so few strike the appropriate chord and catch the attention.

You’re not selling millions of copies of Butcher Baker, but do you feel you and Joe Casey are potentially pulling that off? Are you guys striking the exact chord to catch the greater awareness and influence, or do you feel Butcher simply grabs eyes for its sometimes radical content?

Maybe it’s too soon to tell?

MH: Hmmm. Well, the content: language, nudity, cosmic hermaphrodites, etc, as well as Image’s initial advertising campaign- that sure didn’t hurt the book’s awareness, but if that’s all there was, the book would have failed by issue #2. I think the thing that people respond to is the fact that you can feel a genuine passion in Butcher- the book isn’t made for any larger commercial success, or movie tie-in. As crazy as it maybe, it’s not a cynical book. It’s a big fat love letter to comics and superheroes!

And as far as how people are responding, or what chord it is hitting- that’s probably a bigger mystery for Joe and I than any of our readers. It’s always kind of impossible to see the thing that you are making until it’s over and you can look back at it. I know I get each issue of Butcher and just look at it wondering, “what exactly have we done?”

So maybe it was just a good time, with so many characters becoming commercials for movies, and the earlier insanity of superhero comics being put away, for a book like Butcher to come out and yell about how small we’ve let everything become.

AB: What do mean by “how small we’ve let everything become”? That comics don’t exactly meet the potential they have?

MH: The single comic that comes to my mind when this topic is raised is an old issue of X-Men, an annual I think. In this issue the X-Men go to the South Pole, travel to the Savage land, pass through a magical portal and end up riding in a ancient ship attached to the back of a giant white flying dog. It’s ridiculous and awesome in the way that comics effortlessly can be. That spirit of pure fantasy and real strangeness seems to have left our top hero titles. Now the focus seems almost always to be realism… that’s fine I guess, but it’s boring.

AB: That’s something I always come back to when I review or write about something. I feel comics can go much further, but they rarely really do.

MH: If by “further,” you mean more interesting and taking more chances. The fact is that mainstream comics are a very conservative arena. They sell largely to the same fan base they did 20- 30 years ago, and it isn’t an audience that cries out for change. I mean look at the words spent on the redesign of the DC universe- the suits are basically the same, but now with extra lines in new places. Not exactly a revolution, but in the comic world it’s a big deal.

AB: Alright, let’s go into Butcher Baker. It’s been a year since the first issue was released and at least few months since the latest issue, #7, came out. What do think of that work now that it’s had some time to stew?

MH: Really, I’m not sure what I think about those first issues. Often with my own work I feel like I’m encountering it after the fact just like everybody else. My main reaction to Butcher is “what is this thing??!!?” I still find myself laughing at certain moments wondering if an adult is going to show up and throw the breaks on. Apparently not.

AB: What can you say about the delay on the series?

MH: Ugh. The delay…. The delay is something that professionally is really embarrassing for me. Long story short is that I illustrated a couple experimental projects back to back (Homeland Directive at Top Shelf, and Butcher Baker, the Righteous Maker at Image), while at the same time moving to Europe. Between the projects and the move, my schedule went to hell and when the start date arrived, and even slipped by, for The Strain, I hadn’t finished the first arc of Butcher. Butcher is still coming along though with #8 dropping this summer.

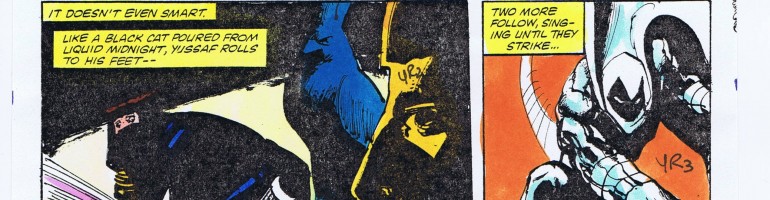

snapshot of issue 8, in progress

AB: Was there ever really a set of self-imposed deadlines on the book, or did you and Joe just approach this as a “it happens when the inspiration’s right” type of project?

MH: There definitely were deadlines. Neither Joe nor I, nor our publisher Image, are “when inspiration strikes” types. The delay is not a happy moment for anybody.

AB: How does your approach on The Strain differ from your approach on Butcher? Looking at the finished product, I would assume you go in with a different mindset.

MH: Yes, my approach on The Strain is totally different. Actually, it’s kind of a return stylistically to my work on The Coffin. As I’ve worked on it, the phrase that has come to mind is a “movie on paper” as opposed to Butcher, which is a surreal pop sketchbook that also happens to contain a great story. So with The Strain, I’m putting a different hat on; I am translating somebody else’s vision, so I want to be respectful of that and be the best director I can.

AB: I went back and re-read Butcher Baker, and something that struck me, more this time than on the initial read through, was the focus placed on contradictions and a sense of the duality in them. How are you contributing to Casey’s idea of contradictions through your artwork? You’re implementing numerous styles … does that play a part?

MH: Truthfully, I don’t know, and honestly I think these are questions sometimes best left unanswered by the artist. When I read reviews of the first seven issues of Butcher Baker, readers had many theories explaining the art choices and how it related to the story. Some were on the mark; some were better than what I had planned. I look back at issues occasionally with these other theories in mind and am surprised to think “huh, maybe I WAS doing that….” So, I have my opinion on why the art is what it is, but it’s not necessarily the definitive opinion.

AB: Reading the book as a whole, it’s clear Casey is interested by the idea of comics being serious yet, simultaneously, comics being disposable. It seems he believes both about comics, and the series almost comes off as a bit of an exploration of that thought, and again, contradiction. What can you say about that debate? Is that something, you too, often consider?

MH: Yeah, where do comics land exactly? In form they are completely disposable: little pamphlets of paper that come out by the hundreds every month. But comics are able to deliver ideas just as effectively as any prose or cinema. Maybe its “disposability” derives more from the content… if it’s superhero book X, it might be more disposable than the latest Alan Moore. …dunno.

This wasn’t something I considered, at least consciously, but I did take joy at trying to illustrate horrible things in a beautiful way. My question was: “how will the reader react if you hand them this horrible toxic present wrapped in beautiful paper and a huge bow?”

AB: What’s cool about Butcher Baker is that wonderfully dressed toxic attitude, yet you guys never seem to let the story suffer because of that. You’re constantly telling the story, still. Not just relying on personality.

MH: Without Joe laying down a good story the attitude and art would be meaningless. There are tons of books with big attitude that suck. Joe’s characters are the key to the whole thing.

AB: How well would you say you mesh with a writer like Casey? I don’t know, reading the book, and knowing the little about both of you I do, it just seems like you’re on a similar page in terms of how you approach creating stuff.

MH: I love working with Joe, and if he ever forgives me for the delay on Butcher I’d love to work with him again. He’s tough and opinionated, but fearless and is a great collaborator. Joe also serves as a great bullshit goalie- a couple times, especially at the beginning, he had questions about my art choices on Butcher, but once we talked and he saw that I genuinely had real ideas about the how and why of what I was doing,, everything was cool. So he’s not afraid to call you on the carpet, but if you can back up your shit he becomes a big cheerleader.

AB: Where Casey leaves off, you do seem to really pick up and actually contribute to the narrative rather than just draw the script.

MH: Well, ideally that is what the art is supposed to do: enhance the narrative. I exaggerate things in the script. It’s like telling a good story- you accentuate the parts that matter and leave the rest out.

AB: Do you find it hard to actually collaborate? You’ve certainly done your fair share of it with guys like Phil Hester, but do you ever think it might be easier to go all out and produce a comic all by yourself?

MH: I love to collaborate and, although like every creative pro I have an idea of someday doing a project all on my own, I think you benefit from the combination of ideas in ways you would never expect. I have a belief in the value of randomness in art… this is an aside, but I make music mixes all the time. I found though that the mix you craft and make just perfect can really suck, but 20 songs on a list playing alphabetically, or by length of song, or whatever, can be really exciting. There are connections you didn’t expect, choices you wouldn’t have made. That’s what collaboration offers you- that chance of random noise that makes things great.

AB: What’s the key, in your opinion, to collaborating with someone? I would think it would take some serious chemistry, and it seems most of comics is more about a writer handing you a script versus actual team work.

MH: For me, the key to collaboration is finding people of like mind to work with. If you want to go hog wild experimenting, but your partner is trying to create the next big superhero team, you might be in trouble… or you might not, who knows?

AB: You obviously use color in your work to great affect. What sort of influences are you drawing from for the color work you do? To me, your approach to color is all pretty new, but I’m an ignorant, young mind. Educate me!

MH: As far as influences for my approach to color, I really don’t have any I can point too. I shop around online and in magazines constantly for palettes and design ideas, but those are all just the elements.

The conceptual influence for the color comes from artists like Bill Sienkiewicz, Kent Williams, and probably, most strongly, Ashley Wood. In the early 90’s, I was a typical fan of the then new Image explosion, but then some new kinds of books, at least new to me, showed up and changed everything: Bill Sienkiewicz’s Stray Toasters, Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum and Kent William and John J Muth’s Meltdown. These painted books were like nuclear bombs going off in my hands and it pretty much decided my course- I was going to do comics, and if I was ever skilled enough I wanted to make books like these.

AB: Do you feel that color evokes something a little more visceral than say page layouts or line art? Would you say color just has a more direct impact on a reader?

MH: For me nothing is more visceral than layouts. Those first few rough lines that hold so much potential for greatness…it’s kind of downhill from there, and at the bottom of that hill usually is comic book coloring. Color done well CAN have a huge impact on the reader, but so often in comics it feels that the line art is treated just as a coloring book. We add color in each spot, not because it makes the page stronger, but because we expect to see every white space filled. So we color everywhere, keep it in the lines, and keep the approach consistent throughout. It’s boring.

AB: True, but there are guys, like Val Staples, who go beyond the job description. And yourself … the color work on Butcher nails that bombast and “lo-fi futureshit” Casey mentions in some of the early back matter pieces.

MH: Well, thanks.

AB: I listened to an interview with Charli XCX today, and she described her upcoming album by saying it sounds like the colors pink, gold and black. Sort of the reverse, but what sound do the colors in Butcher make, if you could describe it?

MH: The colors in Butcher sound like Edan’s album, Beauty and the Beat.

AB: Much of Butcher Baker is a love letter, but while a love letter to the past, it’s also about rejuvenating that old stuff we’ve come to associate comics with – like super heroes. For an artist like you, who’s constantly tweaking his style and pushing forward, what’s it like considering those old things while trying to go forward?

MH: It’s a mixed feeling about the old comics… intimidation and annoyance at once. When you look at the skill level and imagination of someone like Jack Kirby you can’t help but to feel like an imposter, struggling away on your 20+ mediocre pages a month when I think this guy was knocking out 15-20 pages of genius stuff a week! But at the same time you can see how the spell cast by those early artists has frozen the comicbook art form and it’s readers in time- somewhere around the mid 60’s- making the field less and less relevant to the culture at large.

It’s a deceptive state right now as you would think that comics are bigger than ever with the success of things like The Avengers, but the opposite is true. Comicbooks for super heroes are now completely irrelevant. You can be a huge fan of Spider-man, Thor, Captain America, etc. now without ever picking up a comicbook.

So this is a long way of saying that I love the old artists, but it’s time to wake up from the world they made and give comics a new reason to exist.

AB: After asking that question, I realize you have worked on other books which sort of riff on older stuff. The Coffin certainly supplies a Toth or Alex Raymond vibe.

MH: True. I’ve tried to put on older styles to further the storytelling of a particular project. Maybe that is a contradiction to my earlier answer… I don’t know.

AB: Do you feel comic creators hold an obligation to push the work forward all the time?

MH: Well, of course it would be great if everyone was constantly reinventing the wheel and creating unpredictable, challenging new work with each new project, but with the nature of the business that’s just not realistic. Sometimes you have projects that let you stretch and throw out a bunch of ideas, and sometimes you have projects that just getting across the finish line is a victory. It’s a hard enough gig though that I can’t knock anybody; even artists whose work I dislike get a large measure of respect from me just for putting in the hours and effort it takes to work in comics.

AB: So there’s nothing wrong with just doing the job?

MH: Absolutely not… but as much as I say that now you’ll probably catch me in a day or so bitching about someone playing it safe.

AB: What about the people who just write off super hero comics and claim the genre dead? Reading Butcher Baker, I would assume you probably have some beefs with that mindset.

Do you think it’s possible for corporate comics to really do anything inventive at this point or has the battle been fought and lost?

MH: I think corporate comics can still do interesting things, but to do so they have to fight against their corporate instincts. Instead of behaving like a company watching it’s quarterly profits, (which IMO results in projects like Before Watchmen), we need companies to think more like venture capitalists. Invest in the risky ideas so you can find the next Sandman, the next Chew, the next… whatever. We need more of the spirit seen in Vertigo’s early years, or this latest version of Image in comics, and big corporations are the ones in the best position to do it…. IF they have the vision.

– – –

for more on Huddleston, you can check out his blog.